For many doctors it is possible that some of their patients are recording their office visit, with or without permission. In a cross-sectional survey administered to the general public in the United Kingdom, 19 of 128 respondents (15%) indicated that they had secretly recorded a clinic visit, and 14 of 128 respondents (11%) were aware of someone covertly recording a clinic visit. Because every smartphone can record conversations, this may become even more commonplace. The motivation is often reasonable: patients want a recording to listen to again, improve their recall and understanding of medical information, and share the information with family members. A review identified 33 studies (including 18 randomized trials) of patient use of audio-recorded clinic-visit information. Audio recordings were highly valued; across the studies, 72% of patients listened to their recordings, 68% shared them with a caregiver, and individuals receiving recordings reported greater understanding and recall of medical information.

By Glyn Elwyn, MD, PhD; Paul James Barr, PhD; Mary Castaldo, JD, MPH – JAMA.

In the few healthcare organizations in the United States that offer patients recordings of office visits, doctors and patients report benefits. In addition, liability insurers maintain that the presence of a recording can protect doctors. For example, at the Barrow Neurological Institute, in Phoenix, Arizona, where patients are routinely offered video recordings of their visits, doctors who participate in these recordings receive a 10% reduction in the cost of their medical defense and $1 million extra liability coverage.

However, many doctors and clinics have concerns about the ownership of recordings and the potential for these to be used as a basis for legal claims or complaints. Administrators and patients are unclear about the law and are concerned that recording clinical encounters might be illegal, especially if done covertly.

The law is inconsistent: recording is allowed in certain situations and is illegal in others. The goal of this Viewpoint is to help doctors, administrators, and patients understand the law in relation to the recording of clinical encounters and guide reactions to this new phenomenon.

Is it Legal for Patients to Record Encounters?

In the United States, the situation is complex. Substantial effort is made to maximize privacy in clinical encounters. Wiretapping or eavesdropping statutes provide the primary legal framework guiding recording practices and protect against nonconsensual recording of conversations when individuals have a reasonable expectation that their conversation is private. These laws vary at the state level, and these distinctions have significance for patients who wish to record their clinical encounters.

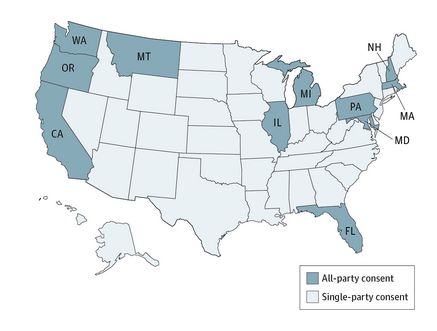

US State-Level Wiretapping Laws

US State-Level Wiretapping Laws

Wiretapping laws differ as to whether 1 or all parties must consent to the recording. In so-called all-party jurisdictions, covert recording (recording without the expressed permission of all parties) is illegal because all who are being recorded must consent. In contrast, in single-party jurisdictions, the consent of any 1 party to the conversation is sufficient, including the person making the recording; therefore, if patients wish to record a clinical encounter, they can do so without obtaining the clinician’s consent. Statutes in 39 of the 50 states and the District of Columbia conform to the single-party consent rule. The 11 all-party jurisdictions are California, Florida, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Montana, New Hampshire, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Washington.

Connecticut requires all-party consent for recording telephone calls, but not for face-to-face conversations. Similarly, Nevada requires all-party consent for wire recordings (unless an emergency precludes obtaining consent from both parties). Vermont does not have a wiretapping statute; however, there is a possibility that nonconsensual recording could be deemed an invasion of privacy in this state. Michigan appears to require all-party consent however, an appellate court interpretation suggests that only a single party’s consent may be required when the person making the recording is a party to the conversation. Because there is some uncertainty with Michigan, we have erred toward a strict statutory interpretation. Oregon law allows for a single party alone to consent to recording of a telephone conversation , but requires consent of all participants for in-person conversations. In addition to criminal penalties, civil liability may occur under wiretapping laws or a claim for invasion of privacy. If sued, the patient could be required to pay for any attorney’s fees incurred by the physician and costs as well as damages .

The consequences of violating wiretapping laws can be severe. Typically, it is a felony to make an unauthorized recording and affected parties also may seek damages from the person who made the recording, including compensation for harm, attorney’s fees, and other costs. Disseminating the recording may be an additional violation, and recordings made in violation of the law may not be introduced as evidence in court.

Are Office Recordings Subject to HIPAA Compliance?

Whether the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) standards apply to the audio or video recording of a clinic visit is based on ownership of the recording. The recording is subject to HIPAA standards if it is “created or received” by a “covered entity,” including health plans, health care practitioners, and health care clearinghouses. However, a patient-initiated recording that is retained by the patient (and not given to the clinician or health plan) is not subject to HIPAA.

How Can Doctors React if a Patient Wishes to Record the Clinical Encounter?

If a doctor in a single-party jurisdiction is asked by a patient to allow a recording, the doctor may ask the patient not to proceed, but the patient has the right to record the clinical encounter. The doctor can choose to continue, accepting that the conversation is being recorded, or terminate the visit. Doctors in single-party jurisdictions should be aware that patients may be recording covertly. In all-party jurisdictions, a doctor can refuse to grant patients permission to make recordings. In these jurisdictions, illegal recording may be reported to the authorities.

Sharing Recordings

Patients are free to share the content of recordings in single-party consent states, but require agreement of those who were recorded in all-party consent states. Most patients use this right to share the recording with a family member or caregiver but not on social media. This freedom may not apply to recordings modified or used to the detriment or harassment of the doctor captured in the recording. Using the recording to harm or damage the reputation of the clinician recorded could lead to legal action by the person affected.

The Future of Recording in Clinic

Research suggests that patients benefit from recording their office visits, and further work is in progress. However, patients who choose to record may be concerned about upsetting their clinicians by requesting permission or may have concerns about retribution if a hidden recording is later discovered. Simultaneously, doctors may be concerned about the possibility of hidden recorders. Both contexts hinder a relationship of trust and open communication. Doctors, patient advocacy groups, and policy makers should work together to develop guidelines and regulatory guidance on patient recording. As health care continues to make significant strides toward transparency, the next step is to embrace the value of recording clinical encounters.

Summary

Digital recording of interactions is occurring widely, often covertly. Doctors and health care systems are uncertain about the law relating to the recording of clinical encounters. Developing clear policies that facilitate the positive use of digital recordings would be a step forward.

July 10, 2017

Editor: Although the publication date of an article may not be current the information is still valid.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Should Patients be Able To Record Their Surgeries

By MELISSA BAILEY, for STAT.

A patient wants to flip on a video camera to capture her surgery while she’s out cold. What should her doctor do? That question is vexing hospitals and legislatures across the country. Patients and transparency advocates say recordings can hold doctors accountable and help hospitals learn from mistakes. But doctors and hospitals raise concerns about privacy, lawsuits, and harm to the doctor-patient relationship.

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, a 672-bed hospital in Boston’s Longwood Medical Area, has noticed an uptick in patients requesting to record medical visits, said hospital spokeswoman Jennifer Kritz. Some want to record a doctor’s instructions or film physical therapy sessions. Others are making a more controversial request to record a medical procedure.

The power of recordings gained widespread attention this year, when a Virginia patient won a $500,000 malpractice suit after a secret audio recording revealed his doctors made vicious comments about him while he was sedated during a colonoscopy.

Attorney Mike Charnoff, who represented the patient, said he has received a dozen phone calls from attorneys and patients seeking to file similar suits. But he said the results are hard to replicate because the doctors’ comments in that case were exceptionally offensive, and because most patients aren’t able to catch them on tape. His client’s cellphone was in the pocket of his pants, wheeled into the room on a cart. That happened only because the surgery was in an outpatient setting, Charnoff said; most surgeries take place in a hospital, in a sterile environment.

In Massachusetts, state law prohibits patients from making recordings without consent: All parties in a conversation must agree to being recorded. Beyond that, Beth Israel Deaconess doesn’t have a policy and has assembled a committee to write one, Kritz said. Several surrounding hospitals said they do allow patients to make recordings, so long as the medical staff in the room consent.

Meanwhile, patients across the country are pushing for more power to press “record.” A Wisconsin state representative, inspired by a man who lost his sister after a botched surgery, introduced a bill this spring that would require hospitals to offer patients the option of recording surgeries.

The National Medical Malpractice Advocacy Association is trying to get a similar measure introduced in Indiana, according to local chapter director Betty Daniels. Mississippi and Massachusetts lawmakers have introduced similar bills in recent years to no avail, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Back when he was a state lawmaker, Boston Mayor Marty Walsh introduced bills in 2009, 2011, and 2013 that would have granted patients the right to film their surgeries. The bills were inspired by a constituent whose mother died during surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. All three efforts failed amid opposition from hospitals’ and doctors’ associations.

The Massachusetts Medical Society, an association of physicians, opposed those bills. In a recent interview, Dr. Dennis Dimitri, the organization’s president, said asking to film a surgery introduces an element of “distrust” between the doctor and patient, because it seems to “anticipate wrongdoing.” Recording “may cause people to be much more guarded about what they say,” he said.

Dimitri also cited logistical concerns: How would the videographer stay out of the way of the surgery? What would prevent the video from getting posted on social media, betraying the privacy of the patient or the medical team?

Patients’ recordings also stand to expose hospitals to more malpractice suits.

But video recordings could actually help the hospital in those lawsuits, argued Richard Corder, assistant vice president of CRICO Strategies, whose parent company provides malpractice insurance to Beth Israel Deaconess and other Harvard-affiliated hospitals. In most malpractice suits, he said, “we never have any way of actually knowing what happened.”

“If we’ve got to defend that practice,” he said, “I’d want to have that recording.” Hospitals could use the videos to learn from mistakes or figure out why one surgeon has a lower surgical infection rate than another, Corder added.

Knitasha Washington, executive director of Consumers Advancing Patient Safety, said any tool that records medical errors can help improve patient safety.

One Canadian surgeon, Dr. Teodor Grantcharov, has designed a surgical “black box”that aims to do just that. The device records not only audio and video, but also hundreds of other medical data points during a surgery, he said.

The black box has been piloted at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, and is set to be tested in two US hospitals next year, as well as in other hospitals in Canada and Europe, Grantcharov said. He said it has great promise to reduce medical errors — so long as it’s used in the spirit of improvement. If the videos are used to “blame and shame” staff, he said, “it will kill the whole safety culture.”

Back at Beth Israel Deaconess, Dr. Tom Delbanco said allowing patients to record doctors’ instructions could be a helpful supplement to the program he co-directs, OpenNotes, a hospital web portal that allows patients to read their doctor’s notes.

Delbanco said that when he was a clinician he actually encouraged patients to bring recording devices to the hospital — for office visits, at least.

Patients immediately forget 40 to 80 percent of what a doctor tells them during an appointment. “And what they remember, they remember half of it wrong,” Delbanco said.

Tech companies are starting to design products to fit this niche.

In Boston, a company called VerbalCare created an iPad app that helps nonverbal patients communicate with hospital staff. Founder Nick Dougherty said VerbalCare plans to add a feature that would allow patients to record what their doctors and nurses tell them.

Dougherty said he found it helpful during an ankle surgery this summer to audiotape his pre- and post-operative instructions, with hospital staff’s permission. While any iPhone can record sound, VerbalCare plans to store the audio in a secure server, where it can’t be manipulated or hacked.

Randy Gonchar, who sits on Beth Israel Deaconess’ Patient/Family Advisory Council, said he also sees a benefit to audio-recording, especially for patients who get anxious in the hospital and might forget instructions.

But he said he worries that doctors might not give as candid advice about a particular drug or treatment. When every word is recorded, he said, “you have to be really, really careful what you’re saying.”

Dec. 15, 2015

Be the first to comment on "Can Patients Make Recordings of Medical Encounters?"